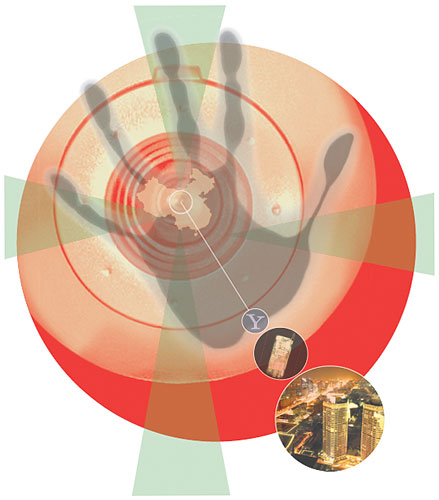

I Was Hacked in Beijing

BEIJING — The reality — and my fears — dawned only slowly.

For weeks, friends and colleagues complained I had not answered their e-mail messages. I swore I had not received them.

My e-mail program began crashing almost daily. But only when all my contacts disappeared for the second time did suspicion push me to act.

I dug deep inside my Yahoo settings, and I shuddered. Incoming messages had been forwarding to an unfamiliar e-mail address, one presumably typed in by intruders who had gained access to my account.

I’d been hacked.

That phrase has been popping up a lot lately on Web chats and at dinner parties in China, where scores of foreign reporters have discovered intrusions into their e-mail accounts.

But unlike malware that trawls for bank account passwords or phishing gambits that peddle lonely and sexually adventurous Russian women, these cyberattacks appear inspired by good old-fashioned espionage.

Recent probes by cyber-countersleuths at the University of Toronto have unmasked electronic spy rings that have been pilfering documents and correspondence from computers in 100 countries. A few patterns have been noted: many of the attacks originated on computers located in China and the spymasters seemed to have a fondness for the Indian Defense Ministry, Tibetan human rights advocates, the Dalai Lama and foreign journalists who cover China and Taiwan.

Although the authors of the reports were careful not to blame the Chinese, a subtext in their findings was not hard to discern: Someone in China — maybe a rogue individual or perhaps a government agency — has been engaged in high-tech surveillance and thievery against perceived enemies of the state.

If that is indeed happening, it would represent a new chapter in the long history of Chinese attempts to manage the foreign journalists who live and work here, who now number more than 400.

The monitoring and manipulation of foreign reporters — the ability to keep them and their sources on edge — would have come a long way since the days when thick-set men in ill-fitting blazers would trail correspondents to interviews, and when unmistakable clicking noises during phone calls gave new meaning to the expression “party line.”

Perhaps most disturbing would be the anonymity of the attacks — the prospect that we and our sources will never know just what we are facing or whom to blame.

Nart Villeneuve, a Canadian researcher who helped analyze the attacks, including an infectious e-mail message designed to dupe the assistants of foreign reporters in Beijing, cautioned there was not enough hard evidence to blame the Chinese, or at least the Chinese government.

“The attackers tend to mask their location,” said Mr. Villeneuve, who is the chief researcher at SecDev.cyber, an Internet security company. “On the other hand, you have to wonder who has the time and interest to produce these kinds of targeted attacks.”

Those of us who live and work in China might be forgiven for suspicions that focus on our hosts, or at least on the legion of so-called patriotic hackers who take umbrage at our coverage and use their computer skills accordingly. While impossible to know for sure, it may have been these nationalistic lone wolves who last week shut down the Web site of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China, the association that represents overseas journalists in China.

To be clear, the lot of the foreign journalist has greatly improved in recent years. But there is an undeniably contentious edge to our relationship with China, one rooted in history and a stubborn conviction held by many Chinese that reporters here are spies with an ability to turn a phrase. (This point was driven home recently by a friend’s mother, who warned him to stay away from me lest he be ensnared by my subterfuge.)

Even if we have scant evidence, most foreign journalists have come to assume our phone conversations are monitored. We have learned to remove our cellphone SIM cards when meeting dissidents. At the office, we often reflexively lower our voices when discussing “politically sensitive” topics.

Is that just paranoia? Perhaps. But recent history provides plenty of examples of government intrusion into the affairs of overseas journalists and their employees. It was only in 2007 that Zhao Yan, a researcher in the Beijing bureau of The New York Times, emerged from three years of detention after he was convicted of fraud. The unrelated accusations that led to his arrest — that he had revealed state secrets — were based on a Times article that correctly predicted the impending retirement of a senior Chinese leader. The state secrets charge, which was far more serious than fraud, eventually was dismissed, but not before the prosecutors introduced documents that had come from a desk in the Times office — an indication that we were never truly alone.

Even now, Western news organizations complain when their employees are called in for tea-drinking sessions with security personnel who ask about the stories they are working on.

The antagonism and surveillance, by most accounts, have become less harsh and blatant over the years. The nadir may have been in 1967, when one of the first foreign reporters allowed into the country, Anthony Grey, a British correspondent for Reuters, spent more than two years confined to a room of his Beijing home. Accused of being a spy but never formally charged, his detention was widely thought to be retaliation for the arrest of Chinese journalists in Hong Kong, then a British colony. They had been detained during a protest, and were released long before he was.

When the author and journalist Orville Schell arrived in 1975, in the waning days of the Cultural Revolution, fear effectively deterred Chinese citizens from having any meaningful interaction with foreigners, whose reputations had been thoroughly maligned by a decade of extravagant anti-Western propaganda. Mr. Schell said that the few times he wandered away from his minders, security officers would find him and escort him back to his hotel.

On one occasion, after he managed to chat up a man tending an apple orchard in Shanxi Province, Mr. Schell was pronounced sick and locked in his accommodations, which at the time happened to be a cave. Even when he managed to pose questions to pedestrians, his queries were often waved away or ignored. “People were almost completely standoffish and unreceptive,” he said. “We foreigners lived in a bubble.”

Restrictions and attitudes relaxed during the reforms of the 1980s but then tightened up again after the student-led protests of 1989 ended in a violent crackdown. Nicholas Kristof, then the Times Beijing correspondent along with his wife, Sheryl WuDunn, recalls early morning jogs shadowed by a small caravan of vehicles. “Sometimes they weren’t very subtle,” he said. “We had lists of all the license plates of the cars that were following us.”

Although Mr. Kristof said they learned to evade some of the monitoring by sneaking out of their building through a stairwell or speaking in code to arrange interviews, he was devastated to find out that one of his closest friends, a Chinese journalist, was actually working as a government spy. “We didn’t really get used to it,” he said of the surveillance. “We were always terrified that a Chinese friend would get into trouble and we had some close calls.”

The Chinese government does not censor the dispatches of foreign correspondents, but the authorities can express disapproval of a writer’s work by withholding visa renewals — a not uncommon practice. In extreme cases, there is always the option of expulsion, which is what happened to a Times bureau chief, John Burns, after he was accused of illegally entering a military zone and taking pictures in 1986. (His interpreter, whose career never recovered from the incident, was jailed for a year.)

Most journalists working in China today would agree that outward signs of surveillance have decreased markedly. Some, however, say that the monitoring has become more sophisticated and subtle, which brings us back to the recent rash of hacking.

Because Yahoo will not discuss the nature of the incidents, it is unclear exactly what happened. The company informed some victims that their accounts had been breached, but declined to be more specific. Were their e-mail messages read? Were their sources endangered? They do not know.

Even if poorly understood, the intrusions have left many reporters, including myself, feeling unnerved. One reporter, a friend with many years of experience in China, said she felt violated and angry after learning her e-mail account was compromised. Even more frustrating, she said, was not knowing whom to blame.

“I worry about Chinese friends who may have written things they could come to regret,” she said, asking that her name and affiliation not be printed for fear of drawing the attention of freelance hackers. “I’d be more relieved if they had just stolen my credit card information.”

By ANDREW JACOBS

Published: April 9, 2010

留言列表

留言列表

【蔡英文說想想】:【中華民國國家作戰系統安全藍圖】

【蔡英文說想想】:【中華民國國家作戰系統安全藍圖】